Five years ago, my son died.

Some months after Isaac’s death in the Beirut Blast, I put pen to paper for the first time to try and understand my grief. My first words were “Five months ago, my son died”. I wrote that these words were so incomprehensible to me that they might as well be in a foreign language. I wrote that I had been without Isaac for 154 nights, and that while time moved on around me, I was still stuck at 6:08pm on the 4th of August 2020.

They say that you should write from a scar, not a wound. When I wrote those first words, they were from a gaping wound. A wound that was still bleeding profusely and had not yet been bandaged, let alone begun to heal.

And now that I have been without Isaac for 1,826 nights? Do I write from a wound or a scar?

I look at the scars that scatter my body. They are constant visual reminders of that night, visual remainders that Isaac is not with me. Every time I look at my face in the mirror, or down at my hands, I see the Blast, I hear the screams. Occasionally, inexplicably, one will throb in pain. Usually one on my left hand, but sometimes others.

But for the most part, they don’t cause agony. I can put them out of my mind and get on with my day.

My grief though? My trauma? They are not yet scars; I can’t imagine a time when they ever will be. But they are also not open wounds. They are more like a scab. A protective layer has formed over the grief and trauma. One that gets me through the day. That allows me to be a professional at work or make chit chat with the parents at daycare pick-up. One that means there are people in my life who have no idea about what happened to me and my family.

But this protective layer is paper thin. Always vulnerable.

Often, I absentmindedly pick at the scab myself. Lying in bed at night, the events play over and over in my head. Or I ruminate on one small detail. Like if Isaac hadn’t been wearing a dark red onesie, would I have seen his wound immediately? Could I have done something different?

Pick, pick, pick. The scab loosens at the edges. The wound begins to weep.

Sometimes, I am going about my day and the scab is knocked unexpectedly. An unintended remark, seeing a family with three boys, noticing the milk expiry date is 4 May, Isaac’s birthday. The knocks can come from anywhere – like running a gauntlet. They can be the tiniest of things, imperceptible to everyone else around me.

Often there is no time to dwell on the pain. I find a bandage, wrap up the part where the scab has come loose, plaster a fake smile on my face and get on with whatever it is that I was doing. Eventually, one of my boys will do something funny, or spontaneously give me a hug and say, “I love you Mumma”, and my fake smile will morph into a real one. The pain will subside, and the day will continue.

Sometimes though, the scab is ripped off completely and the wound will not just weep, but bleed again like in those early days. I have started to be able to predict when this may happen. Anniversaries, Isaac’s birthday, other big milestones that Isaac misses. I know now to expect a migraine. That it will take all my energy to get the kids off to daycare before I retreat to bed until it is time to collect them again. I have some sort of idea of how to get through.

But again, sometimes the knocks can come from anywhere. They can be big – like the bombing of Beirut last year, which triggered a flood of memories and fear. Or they can be seemingly trivial.

Most recently, it was a splinter. A tiny splinter in my two-year-old son’s finger. Levi is usually a pretty brave little kid, but for some reason this splinter sent him into hysterics, which sent me into a spiral. As I tried to calm him down, the fear I saw on his face was the fear I saw on Isaac’s face. His screams were Isaac’s screams. And the screams of the children that I heard for hours on end that night in the hospital. My head began to spin, I struggled to breathe and I desperately tried to shut out what felt like absolutely chaos around me. My nervous system heightened, every little noise felt like a stabbing sensation.

The scab was completely ripped off.

On days like this, it feels like I am back to square one. There is no putting on a brave face and getting on with the day. It takes days, if not longer to get back to some form of equilibrium.

Since Isaac died, I have had many people share with me theories of grief. Stages of grief, growing around the grief, post-traumatic growth, there are many different ideas of how grief plays out. But recently I read the words of another parent that feels like the simplest description:

“I’m fine until I’m not fine, and then I’m REALLY not fine, and them I’m fine again”

The only thing I would add is that my “fine” is not the fine that I was before Isaac died. It is a new baseline. I have had people I know and love tell me that they can see the spark has gone from my eyes. That something fundamental that was there before is gone now. And they are right.

In my early writings after Isaac’s death, I wrote: “Isaac’s death means that my life will never be as good as it could have been, as it should have been. But I refuse to make it worse than it has to be”.

I think I have honoured that statement.

Through sheer guts and dogged determination, Craig and I went from returning to Australia with literally nothing, to making a nice home and securing good jobs, and to ensuring that every single day Ethan and Levi are loved and thriving. To those who don’t know us, we would look like a normal family, a lucky one even. And I have been able to start to live again. For the sake of my children mostly, but also for myself.

In the short time before Isaac died and Ethan was born, some family members bought us a night at the Ritz Carlton. At the time, we were staying in my in-law’s spare bedroom. It was a chance for us to have a night to ourselves, to be pampered a little in between the grief and impending birth. It was a kind and thoughtful gesture; one I won’t forget.

I hated it.

Every single minute I was there, I wanted to leave. I couldn’t relax, couldn’t take in my surrounds, and couldn’t wait to get back to my in-law’s house. The guilt of doing something for myself, of indulging in any form of luxury or comfort when Isaac was dead, ate away at me from the moment we stepped into the hotel until the moment we left. I couldn’t breathe until we were back in that spare bedroom.

This year, in contrast, we went on our first proper holiday as a family. We have travelled in the years since Isaac died, to various places in Australia and to Singapore, but it has always been to visit family. This year, we went on a holiday just for the sake of going on a holiday. For a week in Bali, we stayed in beautiful hotel, ate good food and swam with the kids. It was a far cry from that one night in the Ritz Carlton. As I watched Ethan and Levi’s joy as they explored the hotel, I knew that I was making sure our life is not worse than it has to be. And for the boys, it is even a good, if not great, life. I even started to relax a little.

But the shadow is always hanging over me. Making a bold attempt to try and engage in some self-care, I booked a massage. Sitting in the serenity garden while waiting for my appointment, I looked over a small lake scattered with water lilies, heard nothing but the occasional birdsong, and felt the gentle breeze against my skin.

It was heaven.

But it wasn’t.

Because all I could think was that it wasn’t real. All I could think about was Isaac. And Gaza. And how we create these façades to shield ourselves from the real world.

Pick, pick, pick at the scab.

I no longer write from an open wound. But nor is it a scar. It is a scab – delicate, vulnerable, susceptible to bleeding.

But this is a reality I have started to become comfortable with.

I have great moments of laughter and fun, and most importantly love, with Ethan and Levi. They know of Isaac, they talk about him, they talk to him and tell us they dream about him. They, particularly Ethan, grapple to understand what happened to Isaac, but his death isn’t a dark shadow that is clouding their entire childhood. Their parents are not disengaged, buried in their own grief.

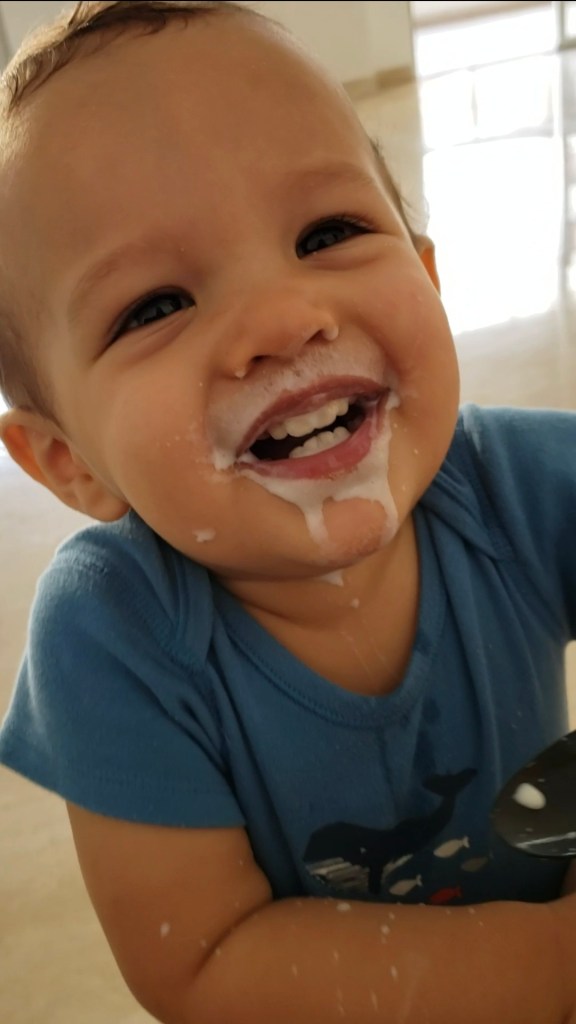

Yet, I also don’t want to stop feeling any pain. The pain is what keeps Isaac close. The pain physically connects me to the moments of joy we had. To the feeling of his cuddles, to the sound of his laughter as he blew bubbles in his milk, to the quiet moments reading stories, and to the crazy moments of him tearing around our cavernous apartment on his scooter. The pain connects me to the person I was with him – relaxed and joyful, truly myself.

When Ethan was born, I struggled to figure out how I could enjoy moments with him, while grieving Isaac. I have learned that joy and pain can exist side-by-side. That one does not negate the other.

A scab is where I want to remain.

Five years ago, my son died. I have now been without him for 1,826 nights. A significant part of me remains at 6:08pm, but a significant part is also here.

I thought of Isaac and you a lot today. I love him and love you, Sarah.

LikeLike

There are no words that can ease the pain or soften the weight of your loss. But please know that Isaac and your family are always in our hearts and thoughts, often present in our conversations. We cannot take away your grief, but we try—humbly and with care—to honour Isaac’s memory here in Lebanon in every way we can.

LikeLike